When you’re on a budget, it’s only natural to be drawn to stores that boast cheap, fast fashion, and Forever 21 has long fulfilled this need for many a penny-pinching college student. While the seemingly endless piles of disorganized clothes and blaring music may initially deter the neat freaks or the faint of heart, this retail giant has given millions of shoppers the unique opportunity to procure armfuls of outfits and accessories while staying well within their spending limits. But whatimplications does this era of “fast food” fashion have for our society?

A recent article in Businessweek by Susan Berfield delved extensively into Forever 21′s history and business practices, and the results are none too surprising for anyone familiar with the rampant violation of labor laws and flagrant disregard for intellectual property that permeates the fashion industry. About 10 years ago, the Asian Pacific American Legal Center and the Garment Worker Center sued Forever 21 on behalf of 19 workers who claimed the company had failed to maintain fair business practices or standard minimum wages. Like many other retail powerhouses, Forever 21 pleaded ignorance to the terrible factory conditions. But Julie Su, the lawyer who had won a $4 million settlement on behalf of 70 Thai garment workers in a separatecase against Forever 21 only a few years earlier, has a different perspective.

“‘It’s impossible to claim ignorance when the problem is so rampant,’ says Su. ’Forever 21 is not a victim of the industry. They create and demand these conditions. They squeeze their suppliers and make it necessary for them to get things done as quickly and cheaply as possible, no matter what the cost to the workers.” – Businessweek

Sadly, these labor violations are even more widespread outside of U.S. factories. And with the 2005 expiration of a trade agreement that had previously limited the amount of garments companies could import from developing nations, the outsourcing of factory jobs has hardly done much for the issue of human rights. Forever 21 has shifted much of its production to Asia, and while Berfield was not able to explore the factories in China and Vietnam, it is safe to assume that the conditions are not much better from what she could see in one of their American factories, which she describes at the end of the article:

“In one, on the top floor, with no company name on the door, about 30 people are sewing gray cotton vests for Forever 21 in a small, hot room. Many of them have stuffed scraps of fabric into their noses to block the particles of material floating in the air. They’re just finishing up a one-week, 10,000-piece order for which the seamstresses earn about 12 cents apiece… If they sew 66 vests an hour, they’ll earn minimum wage. The price tags other workers are attaching read $13.80.” – Businessweek

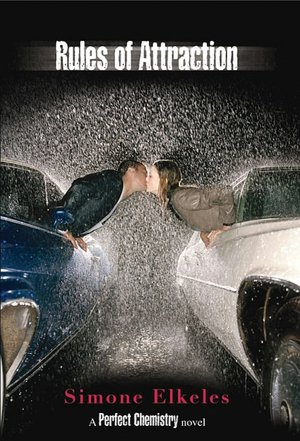

Maxi dress designed by Foley + Corinna, shown here next to its Forever 21 "version" (photocredit to jezebel.com)

Aside from labor violations, Forever 21 has been sued by about 50 companies, including Diane von Furstenberg and Anthropologie, in the last six years for copying their designs. But while big name brands are often able to settle their cases, smaller independent designers are not so lucky. When Virginia Johnson’s lawyer contacted Forever 21 in 2005 about a skirt they were selling whose print was suspiciously similar to the one Johnson had designed and sold at Barney’s during the previous season, Johnson was merely offered 10% of the profits from the skirt.

But here is where my problem lies. Anthropologie and Diane von Furstenberg are way over my budget, as they are for many college students. And even if I had endless money, I wouldn’t necessarily abandon cheap knockoffs for high-end designers, as many of the companies suing Forever 21 have themselves violated numerous labor standards and intellectual property rights. Furthermore, while buying from green and fair trade companies is certainly the ideal, it’s often not the most convenient option, price or location-wise (many times these companies are solely online, adding in shipping costs, sizing uncertainties, etc.). And although I am a diehard vintage fan myself, I understand that thrift stores are hit-or-miss for many people (only one item of everything means it either fits or it doesn’t).

The only solution I can offer is that we should perhaps start thinking about fashion consumption in a different way. We’ve become so accustomed to “cheap and fast” that it’s hard to fight the tide in order to shop slowly, purposely, and ethically, all while staying within our budget. In Berfield’s article, Larry Meyer, the executive vice-president of Forever 21, summed up the attitude of the fashion industry pretty accurately: “‘Every day in retail is another day,’ says Meyer. ‘You never win. You live to sell the next product.’” (Businessweek).

But we can’t live to buy the next product. If we want to be able to go through our day comforted by the knowledge that the cardigan we’re wearing wasn’t produced at the expense of someone’s health, livelihood or uncredited creativity, we need to become aware of the uglier side of the fashion industry. We need to take the time and energy to search out alternative, ethical clothing options that work for our incomes and lifestyles, be it a thrift store, a fair trade website or an independent designer.

We owe it to ourselves and to the workers that make our wardrobes possible.